Farmers, aspiring farmers, high school teachers, and community college instructors got an up-close glimpse of the immense diversity of soil microbes and a better understanding of those microbes’ importance to agriculture, the environment, and society in general. They also got to dig into the kind of scientific tools that make such exploration possible.

A workforce development partnership of UNC Greensboro, Forsyth Technical Community College, the private company Genome Insights, and the nonprofit Veteran’s Farm of North Carolina made that experience possible.

Launched in 2021 and concluded in December, the project was funded by BioMADE, a manufacturing institute sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense to advance the nation’s bioindustrial manufacturing sector.

Dr. Dan Herr, a professor in the Joint School of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering at UNCG; Russ Read, executive director of the National Center for the Biotechnology Workforce at Forsyth Tech; and Laura Kavanagh of Genome Insights led the project, conducting four immersive, hands-on workshops – two for teachers and two for veterans.

The goal: Inspiring the next generation of biomanufacturing workers

Read says, “The goal of the two-day training sessions was to inspire those who will become the next generation of highly skilled bioindustrial manufacturing workers.”

The partnership paired Forsyth Tech’s expertise in workforce development and informal community outreach with JSNN’s advanced technology.

As Herr explains, “We have all these incredible tools at the Joint School that most people in the community would never have access to. And so, this program is helping bridge the formal educational environment with the informal.”

The workshops gave participants insight into those tools used in the science behind bioindustrial manufacturing.

Participants also went to N.C. A&T’s farm to learn about crop and livestock operations, tour the facilities, and collect samples from cow, pig, and chicken compost.

Kavanaugh taught the participants how to load the samples into a portable DNA sequencer, which would run overnight and then provide information about the genetic makeup of microbes living in the samples.

Exploring the vast diversity of life in the soil

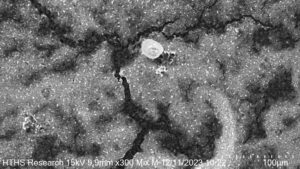

The next day, participants learned to mount samples to view them on a tabletop scanning electron microscope at the JSNN.

In the afternoon, Kavanaugh would share readouts of the DNA profiles of the samples, so participants could see how the microbial species varied in each sample.

“If you look at a soil sample, you might have thousands of microbes, some more adaptable to the environment than others,” Herr explains. “You may find that you have a thousand different types of microbes, but there may be a family of five of them that really dominate the environment, and some of them are probably healthier for agriculture than others.”

If you were to change management practices – adding fertilizer, for example – the distribution of soil organisms would change, Herr adds. “It’s that distribution of microbes that is key to helping understand soil health.”

Technology feeding creative thought

After learning about how the distribution of soil microbes varies, the instructors encouraged discussion.

“A lot of creative thought came out about what they could do with the technology,” Herr says.

For example, the farmers discussed using the equipment to compare what happens to microbes when soil is tilled and when it is not tilled.

“What came out of this was these farmers said, ‘We need a comparative study because we struggle to convince traditional farmers who tilled the soil for decades that you destroy some of the network connections between the microbes and the plants when you till,’” Herr recalls, noting that certain microbes help plants grow.

Robert Elliott, a farmer and educator who leads the Veteran’s Farm of North Carolina, says he stresses soil health when he helps military veterans and service members who will soon be civilians learn about farming.

“I think the workshop opened their eyes to how much life is actually in the soil,” Elliott says. “I can lecture about it all day, but when it gets down to it, it’s a ‘seeing is believing’ kind of thing.”

A broader vision

Herr and Read are still seeing benefits. Graduate students involved in the project received training as well, and they continue to adapt what they learned to other outreach efforts while honing their scientific communication skills.

While the workshops’ focus was soil health, “the vision was broader than that,” Herr adds.

Teachers could have students use the equipment to look at organisms in pond water, stormwater runoff, or a myriad other places.

“The broader idea was giving the participants hands-on experiences where they can tinker and get ideas about biomanufacturing,” Herr says.

“I would say that less than 1% of the population has ever used a DNA sequencer or a scanning electron microscope. Now we’re putting that capability in the hands of farmers and K-12 students,” he continues.

“It’s introducing a new STEM world to these students. It’s a whole different world – a beautiful world.”

Story by Dee Shore, AMBCopy

Photography courtesy of Russ Read, FTCC and Dr. Daniel Herr, JSNN