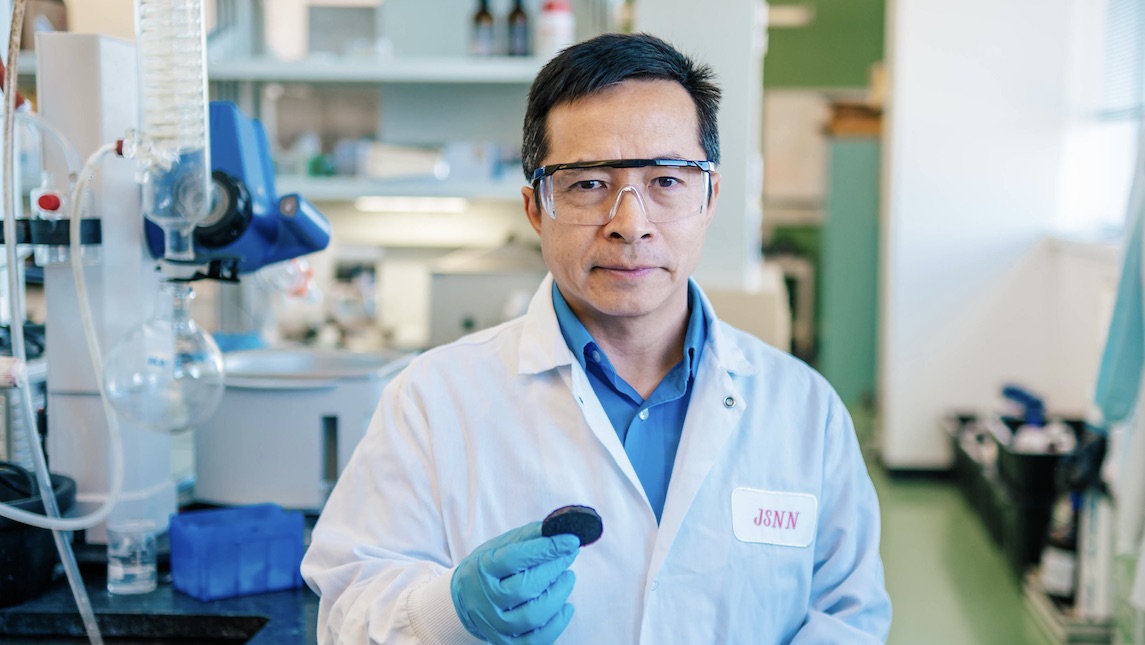

Biochar, a centuries-old technology for enriching depleted agricultural soils, has been getting second looks in recent years as a potential solution to a range of challenges, from making fire-resistant building materials to storing carbon from the atmosphere. At UNC Greensboro, Jianjun Wei is researching ways to make it better at removing lead, mercury and other heavy metals, plus emergent chemicals known as PFAS, from water.

A nearly $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service has funded a two-year project to use biochar created by the Forest Service and make it better at cleaning up contaminated water and resisting fire. Wei is co-principal investigator, focusing on environmental remediation.

The grant, awarded earlier this year, comes as the Joint School of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering is growing its grant funding. As Interim JSNN Dean Mitch Croatt says, “Grant awards for nanoscience at UNCG are moving in the right direction, with a 40% increase over the prior year.”

Wei, a JSNN professor and chemist, is working with postdoctoral researcher Leticia de Moraes and Ph.D. student Sherif Bukari on the biochar project.

What is Biochar? Why is it important?

“Biochar” refers to charcoal made from carbon-based materials, or biomass. It’s a porous material made by burning organic waste — such as sawdust, agricultural residues and manure — in low-oxygen environments.

The Forest Service’s Forest Products Laboratory has been working for 10 years or more to develop production processes for biochar with different characteristics, Wei says. “They are looking for some breakthroughs for applications, and one of their application directions is environmental remediation.”

As the Forest Service webpage explains, the agency sees biochar as a valuable way to use the massive amount of woody residues left in forests after harvesting operations, wildfire suppression, and insect and disease outbreaks.

The Need for a Biochar Solution

Wei comes to the project with a long history of carbon materials work. His research focuses on nanomaterials — ones so tiny that they are invisible to the unaided eye and hard to detect with a conventional microscope — and recently he’s been studying ways to use such materials in environmental remediation. For example, he has explored ways to clean antibiotic-resistant bacteria from water and to detect toxic organophosphates from pesticides.

Wei’s team will use chemicals and other means to alter the biochar to make it better able to adsorb, or bind to, toxic pollutants — specifically, heavy metals ions and chemicals known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

PFAS are often called “forever chemicals” since they persist and don’t break down in the human body or the environment. PFAS have been used since the 1940s in a wide range of products — from cosmetics to non-stick cookware and from food packaging to firefighting foams.

While recent studies have warned that exposure to PFAS, even at low concentrations, may be linked to serious health effects, it’s long been known that heavy metals can be toxic, causing liver and kidney damage, cognitive impairment, cancer, and other ailments.

Removing heavy metal ions and PFAS from water is difficult because they are often present in extremely stable complexes and are not easily biodegradable.

“Because biochar is highly porous and has a large surface area, there are a lot of advantages for using it in the environment to remove such contaminants,” Wei says.

The Challenge Ahead

Still, the biochar needs to be altered to work efficiently. Because PFAS and heavy metal ions differ significantly in their structure, the team needs to produce methods for both contaminants, Wei says.

“If we don’t modify the biochar, it has a very weak affinity, or a specifically selective affinity, to adsorb either the heavy metal ions or PFAS,” he says.

Over the next two years, Wei’s team will work on ways to increase that affinity, first by studying the ways heavy metal ions and PFAS interact with biochar of different surface modifications.

While other researchers have focused on using powdered biochar to adsorb pollution, Wei reports biochar-based panels have advantages for regeneration and reuse. Water would pass through the panels, with the heavy metal ions or PFAS clinging to the surface.

Once saturated, the panels can be treated to remove the contaminants and then reused, he says.

Research, Training Scientists Drive Wei

The project brings Wei full circle to his undergraduate days at East China University of Science and Technology in Shanghai. There, he earned a bachelor’s degree in applied chemistry, with a concentration in water recycling. In the 32 years between then and now, he’s earned a Ph.D. in chemistry and worked in both industry and academia.

Wei joined UNCG’s faculty in 2013, and he’s since won grants from the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the National Institutes of Health, the North Carolina Biotechnology Center, the U.S. Department of Defense, and from industries such as Syngenta, LLC.

Wei was drawn from industry to academia for two reasons.

“Working at a university allows for more freedom and flexibility in terms of my research,” he explains. “I also wanted the opportunity to work with students. Training emerging scientists is a top priority in my research.”

In just over a decade, Wei has advised or mentored 26 Ph.D. students and four postdoctoral researchers. He’s currently advising eight Ph.D. students and one postdoc, including de Moraes and Bukari who are working with him on the biochar project.

Making the World a Better Place

In addition to being committed to training and educating the next generation of scientists, Wei is committed to bringing nanoscience to bear on making the world a better place, particularly when it comes to environmental quality.

He points to statistics that show that a significant portion of U.S. water bodies are considered impaired and below U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards.

The problems aren’t limited to this country. Long-term, the world needs economically viable solutions. “We are hoping to commercialize this research, so that in the end, it has a big impact,” he says.

Story written by Dee Shore, AMBCopy LLC

Photography provided by Sean Norona, University Communications